From the very first Author Earnings Report the efforts of the web-scraping expert known as Data Guy to convince us he has the true sales figures for digital books have been mired in controversy.

Throughout its history, the Author Earnings Report delivered selected insights into the US (and later UK) ebook markets, purporting to know exactly how many titles were sold at what price, but from one report to the next always giving us a different angle, with different presentation methodology, so there was no possibility of seeing a clear picture. A big fail in the eyes of any statistician.

While the Author Earnings Report undoubtedly helped shine a light on the reality that ebooks – especially those produced outside of mainstream publishing, by lowly self-publishers – were grabbing a far higher share of the digital books market than we would otherwise have known, the controversy continued with every new incarnation.

Historical data would be rewritten so suit whatever the latest findings were –

while time and again the numbers simply didn’t add up, and that continued even when the free to access and shoestring-budget-run Author Earnings Report morphed into the deep-pockets-funded, deep-pockets-needed Bookstat.

Deep pockets needed? Hidden behind a ten million dollar paywall –

Bookstat’s questionable statistics became more difficult to challenge as only paying customers were allowed to see them – Data Guy’s last public presentation showing up on the Bookstat website is from October 2018 at Digital Book World.

But come 2020 and the UK trade journal The Bookseller decided to shell out for Bookstat’s top ten ebook chart, which it reports on pretty much every week now.

Not a good move for Data Guy as it exposes Bookstat’s exact sales numbers for the top ten bestselling ebooks in the UK to public scrutiny.

Now that’s no big deal if the numbers are accurate, or if the publishers concerned keep quiet about any discrepancies. But it becomes a somewhat bigger deal when publishers decide to report back to The Bookseller that the real numbers and Data Guy’s numbers are two different planets.

And then came lockdown, a time when interest in ebooks soared, and of course the publishers who have the real numbers at their fingertips, were tracking substantially increased ebooks sales. Bookstat? Not so much.

Rather, lockdown has exposed just how much of a banal guessing game the Bookstat numbers are when it comes to the higher levels of the ebook charts.

Initially The Bookseller reported the Bookstat numbers and then added a little note to the end of the story mentioning that Publisher A or Publisher B had reported different numbers for Title X or Title Y, leaving the reader or TNPS to work out just what that meant for Bookstat’s credibility.

Lately that has changed, and even The Bookseller has been at pains to make clear these numbers are not real, but estimates of questionable value.

On April 28 Kiera O’Brien wrote about the Bookstat vs. publisher discrepancies:

With publishers’ own numbers soaring above Bookstat’s estimates, the e-book market seems to be climbing in sales during lockdown, with demand higher than Bookstat would usually expect. The Flatshare in particular seems to be spiking well beyond expectations. No title in the Bookstat chart, aside from Kindle Unlimited titles, has ever topped 20,000 units, yet The Flatshare sold over that a week ago, according to Hachette, and last week soared even higher, to over 22,000 units. The publisher stated that Blood Orange sold 17,881 units and Rebecca Searle’s In Five Years 8,978 for the same week, all well above Bookstat estimates.

That’s putting it mildly. Across the three titles Data Guy missed around 15,000 unit sales. And that’s just the Hachette titles.

In the most recent The Bookseller report, on May 5, O’Brien decided not to share with us the actual numbers Bookstat had provided, but nonetheless felt compelled to make clear Data Guy’s guestimates were wildly off the mark yet again.

Hachette has stated The Flatshare sold 16,829 units for the week ending 2nd May and Blood Orange shifted 13,809. Again, these figures rank significantly higher than Bookstat’s estimated sales, based on normal buying habits. The e-book boom seems to be continuing through lockdown, or perhaps it was the promise of cut price e-books after the UK chancellor moved forward his decision to remove VAT on e-publications.

The thing is, Kiera, it doesn’t matter whether it was lockdown or the “promise” of the government’s VAT reduction to zero percent (which only came into effect May 1 so would anyway not have affected these numbers).

What matters is that the credibility of Data Guy’s numbers is in tatters .

Data Guy says on the Bookstat website:

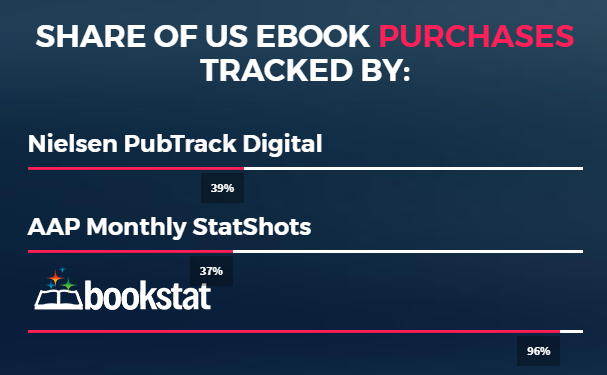

To be useful, sales data has to reflect what your customers are actually buying. When you rely on data that misses 37% of the ebook and audio dollars they spend each day, or 60% of the books they purchase online, you’re flying your business half-blind.

Yet in the first example above Bookstat missed sales of The Flatshare to the tune of 28%. Isn’t that what you’d call “flying blind”, Data Guy?

Data Guy says,

From the largest Big Five trade publishers down to the scrappiest garage micropresses, to sales from Amazon’s in-house publishing imprints and format-dominating Audible Studios to J.K. Rowling’s Pottermore — data that you’ll find nowhere else — even the sales of individual self-published authors: it’s all right there, live at your fingertips, ready for you to ask it the questions that drive your business.

All right there, live at your finger tips? Apart from the thousands of sales that Bookstat totally misses, that is.

Bookstat claims:

When you can see all these ebook and audiobook dollars that others can’t, you end up with a very different picture of today’s market. In many of today’s highest-selling online book categories, the vast majority of these consumer sales have gone entirely unreported. Until now.

The Bookstat website tells us Bookstat tracks 96% of the (US) ebook market.

The corrections issued by publishers in response to the Bookstat numbers published by The Bookseller show that to be a wildly ill-judged claim when carried over to the UK market.

And that’s just corrections from one (or occasionally two) publishers concerning just the top ten bestselling titles. Now imagine even that one publisher’s titles being inaccurately reported across the top twenty / top fifty / top one hundred…

And then try imagine what it means for Bookstat’s credibility if the numbers for other publishers’ titles are equally ill-guessed…

I’ll leave you with this parting thought:

Data Guy says,

Bookstat’s lightning-fast, responsive dashboard lets you search by publisher, genre, author, title, BISAC, ISBN, or ASIN. Discover the top-earning publishers, authors, and titles in each genre right now. See their total ebook, audiobook, and online print sales for last quarter, last week, or even yesterday.

Yet just looking at the examples of mis-guesses on Hachette titles this past month or so we see that, for this one publisher in regard to just a handful of titles, Bookstat has missed ebooks sales in the ballpark of 50,000 or more units.

And no, we can’t blame lockdown. The Bookseller‘s reporting of Bookstat’s top ten bestsellers and Hachette’s real number rebuttals pre-date the coronavirus crisis impacting the UK book market.

Now imagine that appalling margin of error extrapolated over a year.

You really nailed it this time, many thanks!